‘DOC ROCK’ REMEMBERED AS HARD AS ROCKS PROFESSOR

Montana Tech students had a nickname for Geological Engineering Professor Hugh Dresser: around campus he was

known as “Doc Rock.” This nickname was a sign of respect for his notorious reputation as an instructor that pushed his students to their mental and physical limits in pursuit of a highquality, hands-on education that would prepare them to lead successful careers.

Dr. Dresser passed away on July 14, 2023, and those who knew him best say he packed an incredible amount of life into his 93 years, including a teaching career that left a lasting mark on hundreds of students.

“He lived and breathed geology,” said Hugh’s son, Doug Dresser (B.S. Geological Engineering ’80, M.S. Geophysical Engineering, ’82).

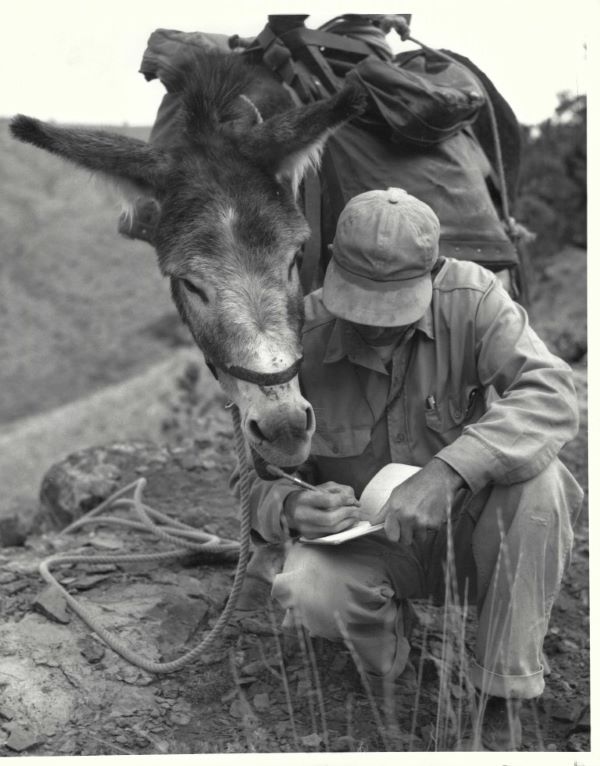

Hugh, the son of Myron Dresser, geological advisor to Exxon’s Worldwide Exploration, earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the University of Cincinnati, where he met his wife, Joyce, before earning his doctorate from the University of Wyoming in 1959. He worked for Carter Oil Company (now Exxon) for a number of years, and even then, it was clear he did geology through his own lens. While others preferred desk work, Hugh convinced the oil company to purchase a truck, which he fit with a horse rack. Dresser purchased a donkey with his own money and took it into the field with him to carry his supplies for days or weeks at a time, as he hunted for petroleum reservoirs in the Muddy Sandstone of Wyoming.

“He was very unique,” Doug remembered. “He loved geology and he did it his way—whether it was buying a donkey to do field work, buying a plane and learning to fly so that he could take pictures to use in his classes, or making his students wear corny 3D glasses so that they could view his lectures in 3D. He was a bit on the gruff side, a product of the Depression, but he showed how he cared by the personal effort he put into teaching his classes.”

Hugh joined the faculty of Montana Tech in 1965. By 1966, the hands-on nature of Doc Rock’s classes had already gained notoriety in the university’s newspaper, with a photo of students scrambling up a rock face, and a report of students “roughing it” and “struggling up steep slopes to Dr. Dresser’s cries of ‘It’s character building,’” on a field trip to Upper Gallatin Valley. Hugh was proud of the fact that he could just about outhike anyone, including his young students, up until his 60s.

“He was known for being a tough teacher,” Doug said. “He wanted to get the best out of everybody. Because of his time with Exxon, he knew what the managers and company men wanted for those students when they hired out of college, so he made his classes so you had to be pushed. He taught to challenge the best students in his class.”

In 1968 Hugh purchased a Cessna 150 two-seater plane so he could take 3-D stereo-photographs. Phyllis Hargrave (M.S. Geology, ’90) remembers taking Hugh’s class where she and her classmates had to wear 3D polarizing glasses, trying to tell Hugh what they saw in his impressive slide collection. He also gave

free plane rides to co-workers and students to observe geology from the air.

“I was intimidated by him at first,” Hargrave said. “But, I learned that he didn’t care what you saw; he cared how you thought, and he tried to guide you the right way. He was the sharpest guy in the world.”

Not everyone appreciated Hugh’s high standards. In addition to rigorous fieldwork and 3-D analysis, students had to be able to write and express their thoughts clearly in essay exams. Not being able to articulate one’s thoughts led to docking of points.

In 1988, Dresser was removed from teaching Physical Geology 101 because of complaints. In a letter to administration he addressed the situation: “For an observational science, illustrations are essential, and over two decades of heavy personal expense and time were invested in producing some of the finest illustrations of geologic

features and processes. Indeed, because many students have difficulty visualizing in three dimensions, the slides were taken and projected in stereo. It may well have been the only stereo physical geology course in the world. Certainly, as an educational experience it stood apart from the traditional physical geology courses taught

at most universities. I like to think that it was one of the courses that students remember, and that it helped to set Tech apart as a special place to be educated.”

Doug Dresser said that once, while he was working in a tiny town in New Zealand in 1996, far from Butte, a petroleum engineer walked in into his office and asked “Are you Hugh Dresser’s boy?” The Canadian said he was proud to have squeaked through Hugh’s Structural Geology class in 1968 and that he would never forget that Bump Coal problem he had to do. Over the years, others relayed to Doug or his father that they were glad for the knowledge they gained, even if the class was difficult.

In his later years, Hugh enjoyed travel with Joyce to places like the Galapagos Islands, New Zealand, Hawaii, and Iceland, all for the rock formations.

“The only places he would ever go was somewhere that had interesting geology,” Doug remembered.

Hugh always had a soft spot for animals. Hargrave recalled one class when Hugh showed up late, which was unheard of. He apologized and explained that he had found a pack rat in his basement, and needed to quickly find it an appropriate home on Pipestone Pass.

Hugh taught his students to appreciate and protect nature.

“We never killed a rattlesnake on any of our field trips,” Hargrave said.

In retirement, Hugh volunteered at the animal shelter in Butte. He would volunteer 3-4 times a week and groom and care for the cats. He was such a fixture that the staff honored him by hanging his photo on the wall with the caption “Hugh’s cat house.” Hugh would also regularly feed the ravens behind the World Museum of Mining.

Whether it was the creatures he tended to or the students in his class, Hugh committed himself to doing what he loved and serving those around him. Doug thought he would like to be remembered as someone who made a difference. “He lived a really good life.”