Beyond reasonable doubt: Mock trial challenges business students to make their case

The large conference room of the University Relations Center was transformed last week into a courtroom, as students conducted a mock trial for BGEN 285- Critical Thinking and Decision Making.

The trial played out not unlike the 1957 classic American film “12 Angry Men,” as a single holdout juror eventually poked enough holes into the prosecution’s case to highlight reasonable doubt, and bring more jurors over to their side one by one. Instead of the full acquittal granted in the film, the jury was hung by the end of the allotted class time dedicated to the trial.

“I think it’s really hard to think that we are putting someone- who many have been in the wrong place at the wrong time- in prison,” Joshua Nelson told his fellow jurors in deliberations.

Assistant Professor Samm Cox (B.S. Business, ’92), a former prosecutor, served as the judge for the mock trial, which was overseen by Associate Professor Rita Spear. Butte Silver Bow Deputy County Attorney Kelli Fivey advised the prosecuting team, while Charlie Smith (B.S. Mining Engineering, ’01) of Crowley Fleck law firm advised the defense.

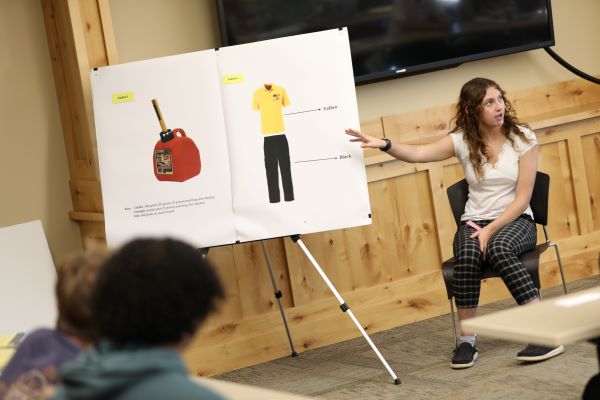

Students were asked to consider arson and homicide charges brought against Alex, a brilliant fictional chemical engineering student at a fictional university who was accused of setting a fire and killing his fellow star student, Carly. Carly and Alex were in the running for a merit scholarship to Harvard University, and the prosecution contended that this was the motive for Alex to set the fire that led to Carly’s death.

Dillon MacIlwraith led the prosecution. His team introduced evidence that included the defendant’s fingerprints found on the gas can used to start the fire, a witness who saw someone in a uniform that looked the same as the defendant’s work clothes at the scene, information about accelerants found in the gas can, and testimony about another fire that was allegedly caused by the defendant in an instance when he came in third place for another academic contest.

“Let’s go to the facts,” MacIlwraith told the jury in his closing statement. “The defendant was willing to do anything to get that scholarship. Don’t let the defense muddy the waters. You are all smarter than that. Find him guilty and give Carly justice.”

The defense did everything it could to introduce doubt. It pinned possible motive on Todd, Carly’s ex-boyfriend, who had a prior DUI conviction. Todd had sent Carly threatening text messages after their break up, and her friends testified that they thought he may have been abusive. The prosecution also noted that Alex worked at a gas station and could have handed any customer the can found at the crime scene. It also questioned whether Alex could have handled the can at all, given that he had a hand injury at the time.

“The state has proven nothing,” mock defense attorney Havyn Boyd said. “The prosecution has not met the burden of proof.”

Most jurors were ready to issue a guilty verdict, but the number of holdouts grew as the Oredigger jury started to ask more questions.

“I don’t think the fingerprints are reliable,” juror Trey Yates said. “He works at the gas station. There’s not enough evidence for me to send a 20-year-old to prison.”

Another juror had a different view.

“You also have to consider that someone’s dead,” juror Luke Bilau said.

The mock trial required students to consider and comprehend the significance of forensic evidence, chain of custody, cross-examination, criminal procedure, jury instructions, and validity of paid expert testimony.

Once the jury was hung, Cox explained to the students what would happen to an actual hung jury. In the United States, criminal convictions must be unanimous. In real cases, the hung juries result in cases being re-tried with a new jury. Prosecutors can also dismiss the cases or make a plea bargain to resolve the matter.

While the trial didn’t end in a unanimous verdict, it showed that Orediggers value critical thought.

“We want them to really think,” Spear said.