Montana Technological University Professor awarded $365,000 NSF grant to study sphalerite in Butte, Philipsburg areas

Photo: Celine Beaucamp with photos of sphalerite.

The National Science Foundation has awarded a $385,000 grant to Montana Technological University Professor of Geological Engineering Christopher Gammons to explore the economic significance of sphalerite, an ore mineral known by its chemical name ZnS, or zinc sulfide.

“We at Montana Tech are excited that Professor Gammons and team are receiving external recognition to continue the long-standing tradition of mineral exploration that is at the core of the University’s identity and history,” Vice Chancellor for Research and Dean of the Graduate School Angela Lueking said. “A successful, competitively awarded NSF proposal, is an indication that the science our faculty are doing has value to external stakeholders and the nation.”

“They mined a lot of sphalerite in Butte,” Gammons said. “It’s second only to copper, with 4.9 billion pounds mined. Twenty-three billion pounds of copper was mined.”

Previous mining efforts targeted sphalerite for its zinc content, but it has emerged as an ore of interest because of the trace minerals also found within. Elevated amounts of gallium, tungsten, germanium, indium, and other elements run throughout the ore.

“Some of these trace elements are critical metals,” Gammons said.

The U.S. Geological Survey has designated many minerals as critical because they are essential to high-technology devices, national defense applications, and green growth-related industries.

“From one perspective, we want to find out if these minerals, in the amounts found in the sphalerite, are economical to extract,” Gammons said.

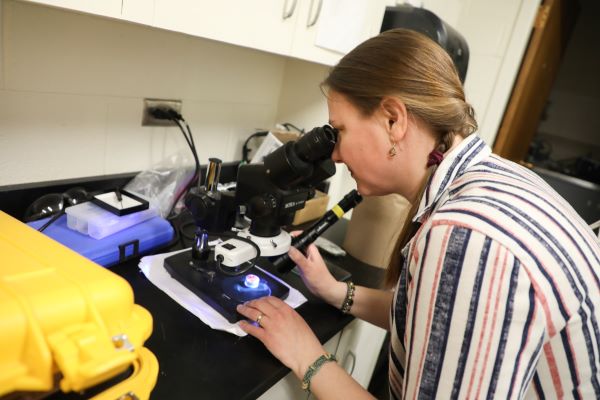

Celine Beaucamp, Professor Gammons’ Ph.D. student, has been studying the Philipsburg Mining District since 2020, including the district’s sphalerite. She and Gammons are studying how the mineral forms, what causes the critical metals to be present in the ore, and how prevalent they are in Butte and the nearby Philipsburg Mining District. To learn more, they are utilizing samples from the Anaconda Collection at the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology. The collection is home to > 20,000 specimens the Anaconda Mining Company collected from 1940 through 1981. The ability to access these specimens is important because many of the mines in the area flooded decades ago, which makes sampling them impossible.

Gammons plans to take the samples to the USGS lab in Denver, Colorado, to be examined with special equipment. He also is applying to explore the samples with equipment in the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource Lab, which should answer more questions about the origins of metal impurities in sphalerite.

“We want to look at the samples at the atom scale,” Gammons said.

Gammons also plans to try to create sphalerite through hydrothermal experiments in his lab in Montana Tech’s Chemistry Department.

“Natural sphalerite samples can contain so many trace metals that are mixed together,” Gammons said. “I want to try to create sphalerite with a known composition of metal impurities.”

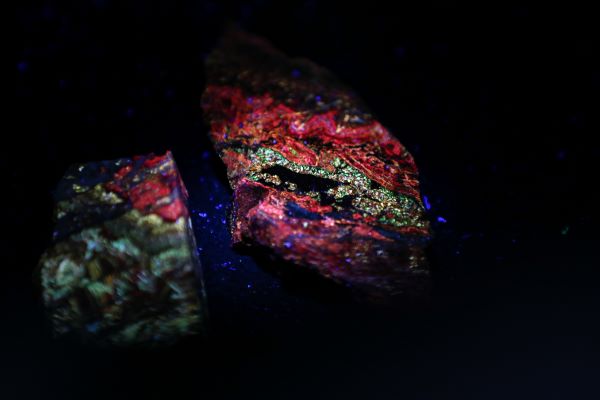

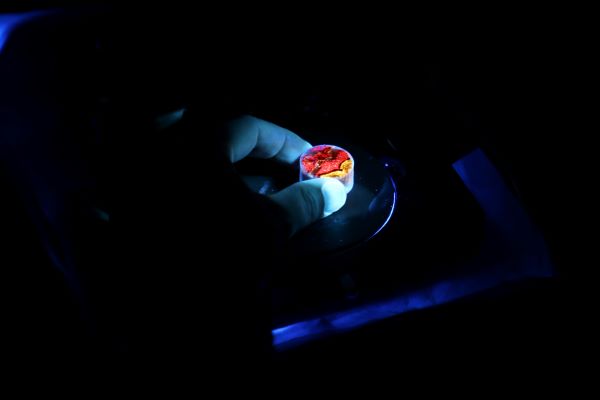

Beaucamp previously created a special dark box highlighting an intriguing property of the sphalerites: when you put them under a UV light, they fluoresce, vivid colors. The rocks look like a metallic rainbow of color beneath the light, and researchers are trying to find out how the different colors of fluorescence relate to their trace metal content.

“When I started studying the Philipsburg Mining District, we didn’t know that its sphalerite had such exceptional optical properties,” Beaucamp said. “It is a nice twist from my original plan. It has been fascinating to try correlating colors with trace elements and explaining this regarding geochemistry and mineralogy. It’s exciting that we now have the means to study this on a bigger scale and extend it to the Butte District.”

The grant funds the project through February 2026. Meanwhile, Gammons has a suggestion for all those rock hounds out there with specimens from Butte who might want to try a fun experiment.

“Go find a handheld longwave UV light to see what it looks like,” Gammons said.